Remembering James H. Smylie

2019 SUMMER ISSUE / GRADUATION

Historical Consciousness

By Stanley H. Skreslet (D.Min.‘80), F.S. Royster Professor of Christian Missions

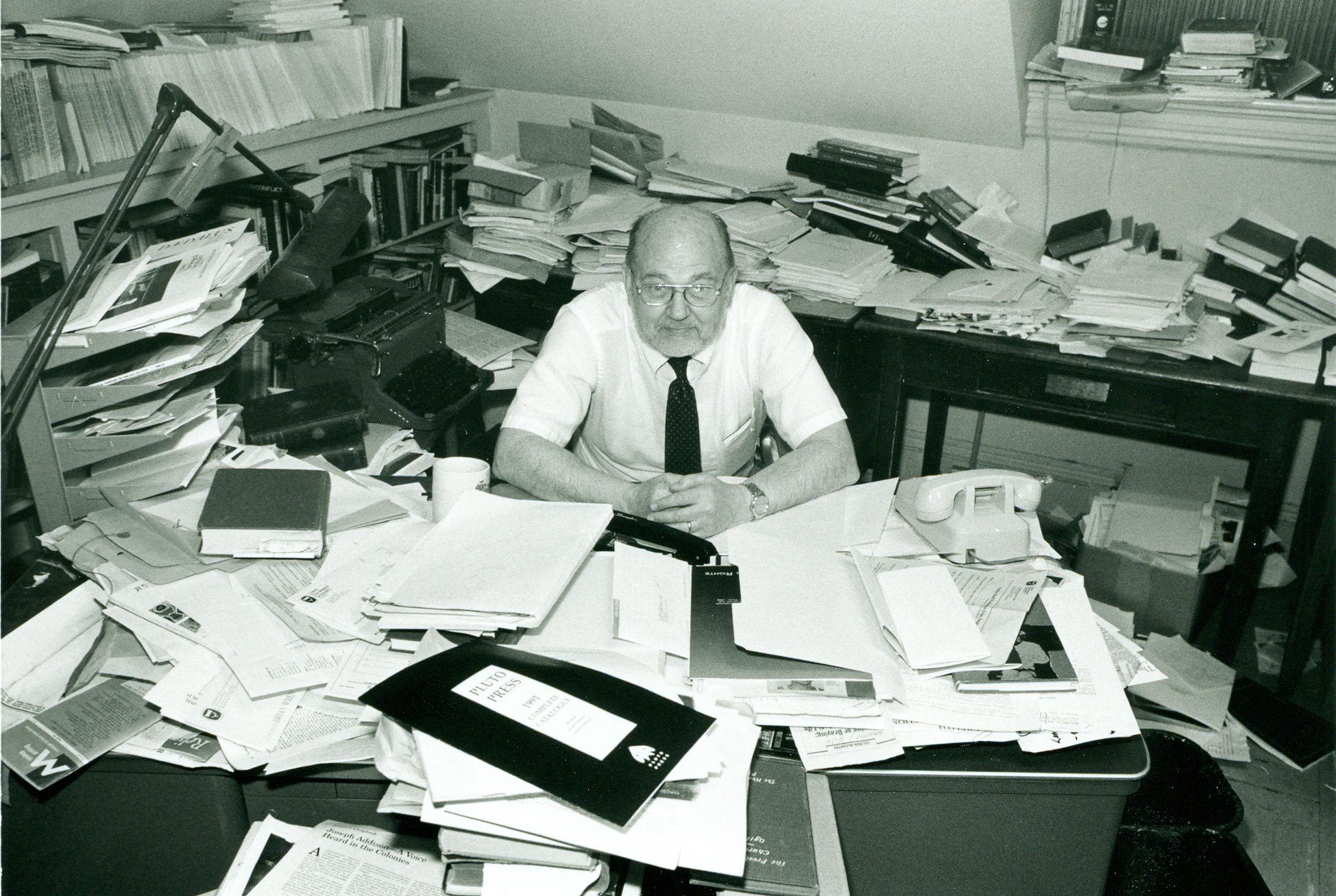

Naturally curious about a great many things, Jim Smylie spared no effort to gather information and then generously shared what he learned with a variety of publics. His office was a testament to his industry, even if a challenge to human mobility. Unsteady mounds of books, papers, and newspaper clippings vied for space with overstuffed filing cabinets and personal mementos. Jim Smylie embodied the historian’s primal suspicion that every piece of physical data touching on one’s subject area could become meaningful, if only placed in its proper interpretive context.

Some packrats never produce anything of their own, content merely to guard hemorrhaging troves of ephemera. Not so with Jim Smylie. In nearly 600 publications, he ranged widely across the landscape of American religious history. Much of this activity was connected to the journal he expertly edited for more than a quarter-century, American Presbyterians: Journal of Presbyterian History.

In a steady stream of articles and book reviews, he often returned to topics related to the subject of his doctoral dissertation, “American Clergymen and the Constitution of the United States of America, 1780–1796.” Through these writings, Professor Smylie carefully considered how America’s religious experience might have shaped the formation of civil institutions in the early Republic, how faith convictions were expressed through political processes, and the role of churches in American public life. Beyond these studies, Smylie wrote on a host of other topics that also deeply interested him, including American literature, art and architecture, Presbyterian missions, films, and the religious culture of Appalachia.

Refusing to be an antiquarian, Jim Smylie moved with ease from his study of past centuries to more recent developments in American history. During his service on the faculty of Union Theological Seminary (1962–1995), he gladly brought his historical sensibility to bear on a thick collection of interrelated controversies that disturbed not a few Presbyterians in the South at mid-century. His writings in The Christian Century and elsewhere helped many outside the region understand better how different church communities in old Dixie were engaging with desegregation, civil rights, urban poverty, the rise of feminism, and the Vietnam war.

On campus, he organized students to talk about these and other pressing issues of the day in anticipation of future conversations they would lead on equally difficult subjects in parishes and other ministry settings. With Ken Goodpasture, Smylie also created a number of experiential learning opportunities for students off campus, including travel seminars to New York City, Appalachia, and Washington, D.C.

My earliest memory of Jim Smylie is running into him on the second floor of Watts Hall. He was urgently searching for a student, perhaps with the intention of sharing yet one more citation to consider or another book to read. Suspecting that his quarry had unwisely decided to take too many biblical electives, he declared to no one in particular, “Students don’t study enough history.” Even so, not a few of those with ears to hear learned from Jim Smylie that historical consciousness is empowering. Without it, one’s context remains a mystery. How else to understand the interrelatedness of faith commitments and one’s actions in the world?