Mandate for Justice: Inside and Outside

“I am a Witness.”

By Rev. Rodney Sadler, Ph.D.

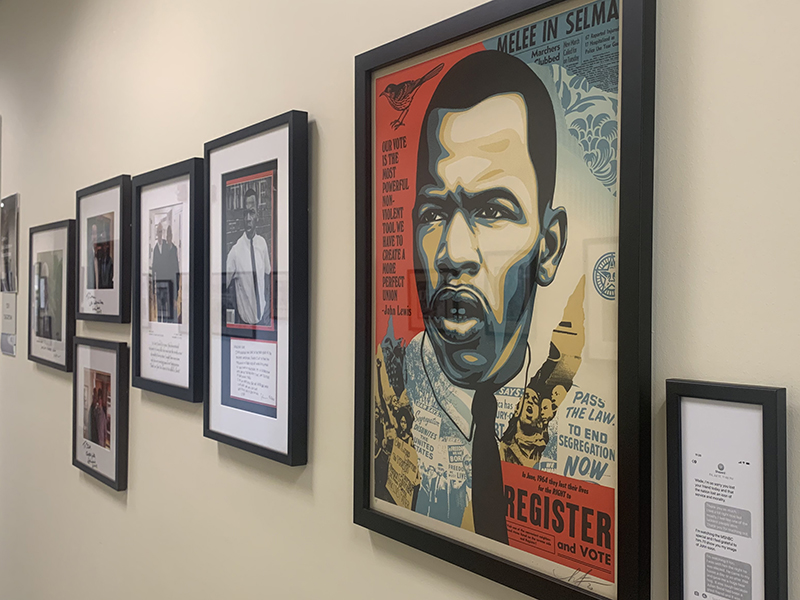

This fall, Union Presbyterian Seminary at Charlotte is pleased to offer an exhibit of historic photographs of the Civil Rights Movement and many of its key leaders. The photographs are all from a collection established by Wade Burns, husband of alum and current Charlotte student Susie Burns. Wade is an unlikely keeper of such treasures, as a Southern white preacher’s kid who spent his professional career as an architect; yet this cherished collection of remarkable photographs chronicles his interaction with many historical figures from the end of the Civil Rights era through today.

Wade grew up in several mostly Southern towns. He moved a good bit, as is common for many children of the clergy. His mother passed away when he was still a child, leaving a void in his life. His father was his moral compass, instilling in him a love of all God’s people and an openness to engage them fairly, beyond the confines of racial identity—an uncommon view during the time in which Wade was raised.

Wade recalls attending integrated schools in Wilmington, North Carolina, when he was a teen and finding high school perilous in that context. Instead of turning from his African American classmates, however, he remembers befriending them, as they protected him from white students who sought to bully him. This kinship with what many would describe as an alien community would turn out to be a formative step in his own personal journey as he began his professional career.

After spending five years in an architectural program at Vanderbilt University, Wade began his career working for L. Miles Sheffer Architectural Firm in Atlanta, Georgia. While there, he was assigned to work on renovations in several sections of the city, including the West End, one of the oldest neighborhoods in Atlanta (it was actually incorporated as a city prior to Atlanta, Wade recalls). His work got off to a rocky start in the early 70s as he sought to help renew a historic neighborhood that was in decline.

Many African American community leaders assumed that Wade was going to follow the common trend of renovating existing housings, selling them to wealthy whites seeking to invest in up-and-coming neighborhoods, and pushing out African American people while destroying their communities. A local community activist began to organize against him and took her arguments as far as Mayor Maynard Jackson. After sharing her fears that he was just another gentrifier, the mayor assured her that Wade was different and had another goal in mind—one of fostering a neighborhood that would maintain the integrity of the community. One in which he himself would live side by side with the residents, many of whom were prominent African American leaders.

Despite the rise in Black nationalism and the politics of division prominent in 1969, Wade continued his work in West End Atlanta. By 1974, he had left his initial firm and started his own, going on to renovate 24 houses in his neighborhood for resale and becoming a national model of a community development paradigm that didn’t seek to displace African American residents. He also got to know his neighbors, including Civil Rights leaders like Julian Bond, Rev. Ralph Abernathy, Ambassador Andrew Young, and a man destined to become his best friend and best man at his wedding to Susie, Rep. John Lewis.

Wade’s time in the community taught him much. He personally experienced the impact of the Southern Black churches on his own theology. For example, he recalls the significance of the pioneer of African American nonviolent activism James Lawson’s concept of grace overcoming unearned suffering and how it was reflected in the durative quality of African American Christianity. He also mentioned the role of James Cone’s comparison of the Christ event to lynching in helping him understand the political implications of Jesus’s ministry. In Wade’s estimation, the Black church offers a necessary perspective on Christian witness from which white Christians need to learn.

To view the exhibit is to get lost in time—to learn from the history of pertinent moments in the Civil Rights struggle, like Freedom Summer; the murder of Goodman, Cheney, and Schwerner; Bloody Sunday; the successful Selma to Montgomery march two weeks later; the freeing of Nelson Mandela; and the election of Barack Obama, among a host of other events. Among the most remarkable photographs are some of Julian Bond, who recounted his youth as a son of a college president and having W.E.B. Du Bois and Albert Einstein come for regular visits to his home; a picture of John Lewis in a hospital bed after the beating he suffered on Bloody Sunday; a photo of King, Young, Lewis, and Abernathy lying on the ground during the Selma to Montgomery march; and a photograph taken by Steve Shapiro of John Lewis throwing a single rose petal in Montreat’s Lake Susan after learning of the death of Julian Bond.

But more than just a walk through history, the exhibit shows a deep and abiding intimacy between Wade and these key leaders, reflected in heartfelt signatures that adorn many of the photographs. It is in these relationships that transcend the barriers fostered by color that transformative Love can be seen—the kind Wade suggests we all might learn to share.

In recent years, Wade has continued the activism of his famous friends—most now receiving their Heavenly reward after valiant lives of self-sacrifice and struggle. He calls himself an “accidental activist” who happened into a scenario that changed his life forever. He has continued their work and inspired countless others, including a plethora of young people at places like Montreat, to join the movement for justice. The exhibit is a challenge to all who view it to recognize that change comes from ordinary people standing up and working to overcome evil and injustice in this world as coworkers with God.

This exhibit of an ordinary man deemed white who surrendered his privilege to stand arm and arm with Black activists is a challenge to all to know that we each have a role to play if we would like to see a better world. It is a call to engage in a struggle that is bigger than any of us, but worthy of all of us. It offers an imperative to each of its viewers to get involved in this necessary work.

The exhibit “I am a Witness.” is located on the second floor of UPSem Charlotte outside the doors of the Center for Social Justice and Reconciliation office. It will be open to the public in the fall of this year.

Rodney S. Sadler Jr. is an ordained Baptist minister and is Associate Professor of Bible and Director of the Center for Social Justice and Reconciliation at Union Presbyterian Seminary. His teaching experience includes courses in biblical languages, Old and New Testament interpretation, wisdom literature in the Bible, the history and religion of ancient Israel, and African American biblical interpretation. His first authored book, Can A Cushite Change His Skin? An Examination of Race, Ethnicity, and Othering in the Hebrew Bible, was published in 2005. He frequently lectures within the church and the community on Race in the Bible, African American Biblical Interpretation, the Image of Jesus, Biblical Archaeology, and the Dead Sea Scrolls. He is the managing editor of the African-American Devotional Bible.