Movement Toward Diversity

Under President Benjamin Rice Lacy, pressure for change at Union itself began to be felt. In November 1934, a student group petitioned the Seminary to have colored delegates to an inter-seminary conference as “guests under our roof.” President Lacy was pleased to invite the students to the campus for the meetings, but stated that they had to stay overnight at the historically black Virginia Union University. Virginia law prohibited any integration of the races in any Commonwealth school.

Across Brook Road at PSCE, familiar segregation patterns continued to be the norm, but they were being questioned by concerned individuals or small groups of people. Louise McComb writes:

One day there was a decision at ATS of momentous proportions: to invite a visiting churchman, a black man, to have dinner in the dining room. The decision was made with the knowledge that it would present a delicate situation which could have resounding repercussions for hundreds of miles beyond the dining room, mainly in a southerly direction, if not handled discreetly. Carefully selected students were approached and asked if they would sit at the same table. Two students (the writer one of them) were asked to serve this table. All accepted, recognizing the honor of being asked to participate in this precedent-breaking meal. The result: a pleasant meal which gave no evidence that an accepted pattern had been quietly smashed.28

This small incident provides a yardstick with which to measure the progress in this area that took place in succeeding decades. It also illustrates ATS President Edward B. Paisley’s determination to take decisive steps in doing what he could to bring about social change. He had already taken a personal stand against the segregated policies prevailing at the Montreat Conference Center. McComb reports that when black Commissioners to the Presbyterian General Assembly had to eat in the pantry, he went there and ate with them.

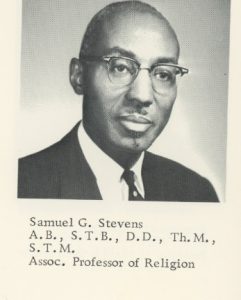

One month after that meeting, Samuel Govan Stevens, a graduate of Lincoln College, wrote to President Lacy seeking admission to the Th.M. program at Union. In 1937, Stevens became the first African-American Union Seminary graduate.

The interpretation of these events was also changing. Professor Ernest Trice Thompson taught church history for over 40 years, but he was not interested in studying the past for its own sake; he saw in history a means to encourage involvement in current issues and “light the way toward a better future.”29 In the March 21, 1949 issue of The Presbyterian Outlook, Thompson published a landmark Bible study arguing that racism was unbiblical.

A few years later, a committee of the Board, prompted by student, faculty, and administrative support, made a significant decision. The committee made it clear where they thought Union should stand and presented the Board with a positive policy: A Brief Statement of the Practice of the Seminary in Educating Negro Students (April 4, 1956). The committee recommended admitting and housing all qualified students regardless of “racial origin.” The committee’s statement was a witness to major change:

The Christian Scriptures indicate that racial distinctions have no place within the life and fellowship of Christian believers. Nowhere in the Standards of our Church are there any teachings which justify us in drawing racial distinctions within the Church itself … there is no alternative but to offer to qualified Negro students the full facilities of our Seminary as they prepare themselves for leadership within the life of the Church.”30

The Board adopted the recommendations unanimously. The recommendation to engage all students without regard to race signaled a transformation in theology that challenged “The Spirituality of the Church” doctrine.

The attitude that the church should stand silently aloof from the ethical conflicts of modern life had become incomprehensible to many biblical theologians. A booklet celebrating the centennial of the Seminary’s move to Richmond observed that the teaching students received at Union “grounded us in Reformed Theology, not as an academic discipline alone, but as fuel for illumining the public life of the troubled and hopeful days through which we were living, as well as of the fourth century when the Nicene Creed was formulated.”31 Union’s tradition, reinterpreted in the face of change, was enabling its graduates to respond to the times.

28. McComb, 37-38.

29. Peter Hairston Hobbie, Ernest Trice Thompson : Prophet for a Changing South(Ph.D. dissertation., Union Theological Seminary, 1987), 541.

30. Board of Trustees, Minutes, 1950-59, 803.

31. “A Century in the City,” celebrating the centennial of the move of Union Theological Seminary from Hampden-Sydney to Richmond (UTS, 1998), 12.